“Begin at the beginning," the King said, very gravely, "and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

―Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

This advice, coming from the King no less, seems obvious, maybe even a truism, but in chess we’re often told to do the opposite:

In order to improve your game, you must study the endgame before everything else, for whereas the endings can be studied and mastered by themselves, the middle game and the opening must be studied in relation to the endgame.

—Capablanca

In contrast, Capablanca’s advice has a pleasingly contrarian logic. Start with the end. It’s just counter-intuitive enough to feel profound, yet simple enough that you can understand it right away. It makes you feel like you’re in possession of a secret.

Such insights should be regarded with a healthy dose of skepticism. What is clever is not necessarily true. Apart from being too pat, the Capablanca quote does not seem to be literally true. You certainly can study the opening and middlegame without explicitly relating them to the endgame, and get a lot out of it, too!

But the biggest issue with starting with the endgame, by far, is this:

Most games between beginners do not reach the endgame at all!

Can it really be optimal to focus your study on a part of the game that rarely occurs in your own practice? I sometimes feel that the advice to not study the opening reflects a certain lack of empathy. It’s easy for experienced players to forget how disorienting and discouraging it can be to start the game with no idea what to do.

Many admonitions to study the endgame seem less about improving your results and more about some sort of moral obligation. This comes to the fore every time a top player makes a big mistake in the endgame.

In this position Maxime Vachier-Lagrave dashed out Rxg5+?? After the response Kxg5, Black had the opposition, meaning White’s king would be forced aside, leading to a loss. Rather than taking the rook, Kf4, or almost any king move, would have held a draw.

While this particular instance was clearly the culmination of some kind of months-long tilt MVL has been going through, there’s always a big outcry whenever a top player messes up a theoretical endgame. This was a simple one that even beginners know, but some theoretical endgames are quite subtle and difficult to get right. Nonetheless, there seems to be a common agreement that losing because you forgot something you could, in theory, have memorized, is more embarrassing than losing because you played like shit. There’s something about the endgame that goes beyond winning and losing and into notions of character and discipline.

The implied argument seems to go something like this: Studying the endgame is so boring, it must be good for you. I disagree with both ends of this argument: I find the endgame fun, and I don’t think what’s boring is good for you.

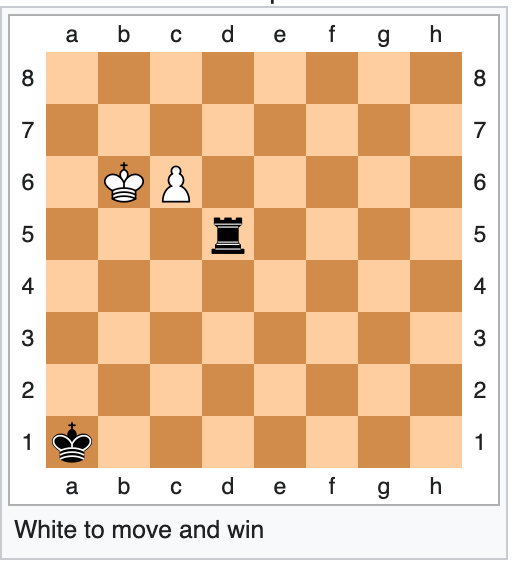

The fun of the endgame consists in the way intricate richness and complexity can spin out of a seemingly simple position, as in perhaps my favorite chess position of all time, the “Saavedra Position.”

The endgame presents an arena where it’s possible for relatively inexperienced players to analyze and arrive at concrete conclusions, as compared to the middlegame, where most of the time many moves are possible and evaluations are quite murky. Maybe even more importantly, the endgame is an opportunity to feel out the geometry of the pieces. The simplified nature of the positions seems to distill the essence of each piece. These more poetic justifications for studying the endgame are hard to support with data, but I find them more convincing.

The endgame is also dramatic, in the sense that a razor’s edge separates a win from a draw or a loss. In competitive terms, the endgame is winning time, as basketball players call the final minutes of the game.

Regarding boring or unpleasant study, in Chess Improvement by Barry Hymer and Peter Wells I found much that I agreed with, but this part did not square with my experience:

“The road to chess improvement, as in other domains, is tough, structured, and probably not enjoyable.”

Many of us go through the same evolution with regards to unpleasant or difficult study. As a child, you try to avoid boring or unpleasant activities. At some point, you realize that to get really good at something, sometimes it’s necessary to do work you don’t particularly enjoy. From there you might make a further leap: that the value of work is in fact directly proportional to how unpleasant it is, so the way to mastery lies in seeking out unpleasant tasks. “No pain, no gain” becomes “pain is gain.”

Yet this attitude can be just as limiting as avoiding hard work altogether. Chess is, after all, a game. Having a playful mindset helps you see opportunities and bounce back from losses. Playfulness also fosters creativity, which is not merely nice to have, but absolutely necessary to play at the highest level. Finally, chess improvement happens in months and years, not days and weeks, and a rigid focus is difficult to maintain for a long time.

Since coming back to competitive chess a few years ago, I’ve increased my USCF rating from the high 2200s to over 2400. Living in Boston, many of my rated games are against ambitious juniors rated 2000-2200, and let me tell you, those little monsters are not that easy to beat! In this period, almost all of the work I’ve done on chess has been enjoyable.

You know what’s hard? Taxes. Kubernetes. Chess is fun.

Maybe chess is more fun because it comes relatively easily to me, or maybe my talent for chess consists precisely in liking it. As a chess coach and content creator, the most frustrating thing to me is that hardly anyone seems to like chess as much as I do.

On the Homeroom podcast with Sal Khan, Magnus Carlsen said that his chess pursuits as a kid had no particular structure, he just studied what he liked. Maybe the best advice then is to study the endgame if you like it.

Great stuff Nate- I'd love to read a post/hear more about how you went from 22s to 2400!