Q: Hi. I’m a fictional chess enthusiast. In order to spice up the structure, this week I’ll be leading a little question-answer session.

A: Okay, that wasn’t a question, but the idea sounds promising.

Q: Right. Last week you said you were starting a series on common mistakes. What’s on the menu this week?

A: Studying too many chess books at once. On the How to Chess podcast, Omar Mills, an adult who got hooked on chess after watching The Queen's Gambit, offered a piece of advice: Don't buy any books. This might sound strange at first, but he’s got a point.

Q: What's wrong with chess books?

A: Nothing, really. But getting good at chess, like anything else, requires a combination of knowledge and skill. Having too many books puts you at risk of falling into what I'd call the "knowledge trap." This happens when you believe knowledge alone will get you to the outcome you want, and you neglect to develop the skills that compliment the knowledge. What makes this trap so seductive is there's always more knowledge to be gained. Especially if you have a shelf full of chess books, there's always another book to reach for, more knowledge to be acquired. And this knowledge might very well be accurate, interesting, and valuable -- at some point. But if you never develop the skill, your chess performance is unlikely to improve much, no matter how much knowledge you gain.

Q: Okay, but chess is a thinking game. Why won't more knowledge help?

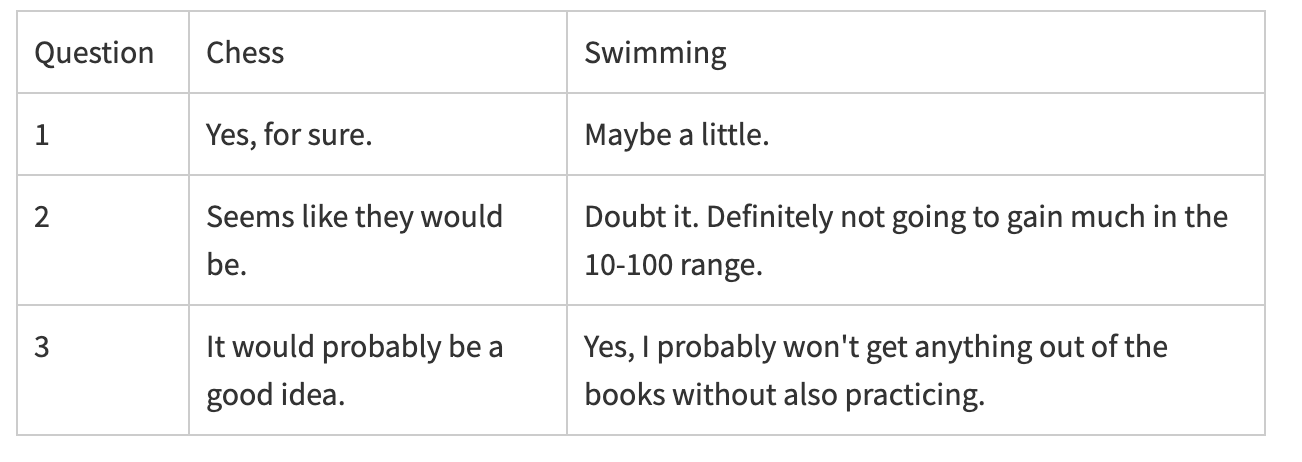

Think about how you would answer each of the following questions for A) learning chess and B) learning how to swim.

Would reading books on the subject be helpful?

Would more books be more helpful? How much better would ten books be than one? What about 10 vs. 100?

Would it matter if you practiced doing the skill while you were reading the books?

My initial intuitive answers would look something like this:

In the case of swimming it seems very obvious that books won't help you much if you never get in the pool. But what struck me when thinking about this comparison is my actual experience of learning chess more closely resembles my intuitive answers about swimming. That is, we tend to think of chess as an intellectual activity where knowing more stuff will really help, but it's not clear that it actually plays out this way.

Q: I've heard stories that Bobby Fischer and Magnus Carlsen read an enormous number of chess books as kids. Shouldn't we follow their example?

A: Yes, that's interesting, but there are a few sticking points.

First, they were probably also playing an enormous amount of chess at the same time. So they were constantly practicing and experimenting with the knowledge they were gaining.

Second, I believe their default mode of engaging with chess books was furiously active. They were constantly probing and questioning what they read. In a sense, they were always "playing through" the books. For most of us, we might need more support to maintain an active mindset.

Q: But I like books!

A: Well yes, this is a very good reason to own chess books! Reading books for fun is great. But it's unlikely to improve your competitive performance unless you back it up with lots of practice as well.

Q: Okay, how do I get more out of reading books?

A: First of all, stick to one book at a time. Maybe two. But any more than that gets very hard to keep track of. You can't back up the material you're learning with sufficient practice. Even keeping up with the logistics of what you're supposed to be learning gets really tricky. Finish the book you're working on before moving on to the next book.

Second, make a simple plan to practice what you're learning. For example, if you're reading a book on a certain opening, arrange a training match with a friend where you both agree to play that opening. Or if you're reading a book about Capablanca's endgames, play out some practical endgames from the book.

Third, focus on books that aren't too hard. Many players work on books that are far too hard for their current level. I'm not even talking here about notoriously hard books, like Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual or Aagaard's Grandmaster Preparation series. Most people who start these books know what they're getting into. But there's a wide gulf between these and what's most efficient for club players. A book can be much easier than Dvoretsky and still too hard for your current level.

There’s a common misconception that fuels both the desire to study many books, and to study very hard books: that getting good at chess is primarily about mastering deep and intricate ideas. There are some deep ideas in chess, and they're fun to learn about, but succeeding in competitive chess is (mostly) not about deep ideas. The things that decide most practical games are relatively simple: get your pieces out, know some typical plans for the position, stay alert for tactics, don't blunder anything, manage your time. Staying on top of these things doesn't usually require deep or complicated ideas, but it does take a lot of practice.

Wonderful article. Please keep up your great writing

Guilty as charged.