Zwischenzug is a newsletter for smart, curious chess players. To have it delivered weekly to your inbox subscribe here:

A few weeks ago when I encouraged club players to take up mainlines part of my reasoning was that most of your opponents won’t be that booked up, so the amount of knowledge needed to play the opening is less than you think. I heard back from several club players that actually many of their opponents are extremely booked up.

Now obviously these players know a lot more about what’s going on in their own games than I do. At the same time, my impression from my own games, student games, reader games - basically all the games I see on a regular basis - is that players are usually improvising from an early stage in the opening, and few games are decided by who remembers more moves in a theoretical variation.

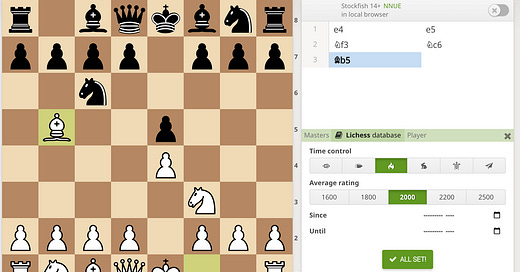

To get to the bottom of this I decided to do a little experiment. I opened up the Lichess opening explorer, put the starting position of the Ruy Lopez on the board, and adjusted the explorer settings to look for blitz games in the 2000 rating range.

According to analysis by Chessgoals, 2000 Lichess blitz is roughly equivalent to 1700-1800 USCF or FIDE. When it comes to opening knowledge I figured the time control doesn’t matter much - if the players knew the position they’d bash out their preparation whether it was blitz, rapid, or whatever.

Then I looked at the top eight recent games that Lichess shows for the settings I chose. I didn’t cherry-pick the games - I just looked at the first games that came up. This should be a fairly random sample of games at this rating level.

I made a study of the games and my analysis of the openings. Check out the study if you’re interested in the details of the games. In the rest of this post I’ll summarize my findings.

Book Moves

In the eight games I looked at, none made it past move 10 in what could be considered a “book” position. The games exited mainstream theory at moves 3, 4, 4, 7, 5, 9, 5, and 10 respectively. That comes out to an average of just under 6 moves of theory per game. Given that the Ruy Lopez starts on move 3, you’d have to say that on average the players weren’t very booked up.

For this survey I wasn’t picky - I considered it “theory” as long as it had any reasonable traction in master games. In the study I marked the move where the game exited common theory with the novelty notation N. In this case N doesn’t necessarily mean the move has literally never been played before by anyone, just that it could not be considered “theory” by any reasonable definition.

Another thing you might wonder - did the player who deviated from theory fare worse? As it turned out, no. Out of the 8 games the player who deviated from theory first scored 4/8, exactly 50%. Who got out of book first did not have any correlation with who ultimately won the game.

The important question is not if your opponents have sometimes memorized long lines. It’s whether you need to memorize lines to avoid getting killed. Given that on average the players did not follow many book moves, and the player who deviated from book did not seem to be punished, my conclusion is memorizing lots of long lines has limited value and certainly isn’t necessary.

Move Order

A particularly common way the players exited the accepted theory was by playing the usual moves but in the wrong order. Especially thematic for the Ruy Lopez, Black players often picked inopportune moments to kick the bishop with …a6.

Most Ruy Lopez players probably know that White can’t just win a pawn in the mainline of the Ruy Lopez after 3…a6 with Bxc6 and Nxe5 because Black will get the pawn back with a queen fork:

But this doesn’t mean Black can always play a6 with impunity. In other positions, White can win a pawn this way, in particular if White has already castled or defended e4. In both of the following positions Black has just played a6 at a bad moment and White could win a pawn for free with Bxc6 followed by Nxe5.

Interestingly, White did not take advantage of the opportunity in either case. This suggests to me that the players misremembered because they weren’t following the logic behind the moves. If you look at the last two positions as puzzles it’s not hard to figure out that Bxc6 works, but presumably the players were on autopilot, or under a mistaken impression that a6 is always safe to play in the Ruy Lopez.

Opening Principles

The main opening principles, to my understanding, are these:

Control the center

Develop the pieces

Castle quickly

I found many examples where players violated these principles, often leading to disaster. Let’s look at some examples of each.

Control the Center

In this position White moved away from the center with Nh4 (“a knight on the rim is dim”). Standard development with Bf4 or Be3 would have been a better idea.

Bring out the pieces

A corollary to bringing out your pieces is that you should not move a piece twice before all your pieces are out unless there’s a tactic. Here Black played Bh5, moving the bishop a second time before finishing development. Better would have been 0-0 (developing + castling).

Castling

Here White played dxe5. It would have been better to castle, since Black is nearly in zugzwang anyway. Later White’s king being in the center allowed Black to complicate the game.

Many players are reluctant to castle unless there is a clear, immediate danger to their king. Likewise, many players are reluctant to develop a piece unless it serves a clear, immediate purpose like creating a threat. But the whole point of principles is that they serve as guidelines for the lines you can’t see. By the time your king is under direct threat, it’s often too late to castle (you might be literally in check). When a tactical melee arises, you’re more likely to come out on top if your pieces are developed and coordinated. Even the strongest grandmasters can’t foresee every contingency. The point of the principles is they make it more likely things will work out for you in the variations you haven’t seen yet.

There are lots more examples in the study. Overall though the frequency of these mistakes reinforced the idea that memorizing long theoretical lines isn’t necessary to survive. In these games, consistently following standard opening principles would have been enough not only to survive, but in many cases to gain an advantage.

The biggest overall pattern I noticed in all the games is that players were too anxious to do something violent before bringing out their pieces and castling. It might sound like a cliché, but getting every piece - literally every piece - involved in the game before going on the offensive really does give you the best chance to succeed. I think of this as the Morphy strategy because Paul Morphy used it to dominate an entire generation of chess players. If you really understand this and your opponents don’t, you can still use it to dominate today.

In this experiment I honestly tried to stack the deck in favor of book lines. I chose the highest rating range that could reasonably considered intermediate club players. At least one player in the study was rated over 2200. Many OTB experts and masters are not rated any higher than this on Lichess. I also considered any move that had any sort of following in master games to be theory. Nonetheless, the games simply did not follow opening theory for very long.

This raised another question: if most games don’t follow the theory, what makes mainline openings so intimidating? I think it has less to do with the openings or the games themselves and more with the sources that teach them. Books or courses on offbeat openings like 1. b3 or the Scandinavian tend to present them as easy. Sources on mainline openings like the Ruy Lopez tend to emphasize how complex and rich they are. This creates the impression that you need to know an enormous amount to even start playing mainlines.

While it’s true that the Ruy Lopez does contain a lot of complexity, what this experiment shows is that you don’t need to memorize an enormous amount to get started. At least up to 2200 Lichess (and probably beyond) if you follow opening principles, know the most common middlegame plans, and are alert to tactical opportunities, you have every chance of scoring well.

Got a chess friend who might like this post? Use the button below to share it!

Very nicely written. I’ve never worried too much about not knowing “theory,” but your analysis is very helpful, particularly the emphasis on knowing principles, rather than memorizing moves. As Emerson said, “As to methods there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The man who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble.”

Awesome post, my plan now is just to start moving random pieces around for the first few moves and follow the opening principles. I'll let you know how the experiment goes.