Is there a fundamental law of chess? According to Find the Right Plan with Anatoly Karpov, there is:

“Restricting the mobility of your opponent’s pieces (and in association with this: domination by your own) - is the most important law of chess.”

I was all set to dunk on this passage for being excessively reductive - in general, I think chess improvement is to be found more in practice and patterns than in laws - but the more I think about it, the more this idea makes sense.

Isn’t this precisely what AlphaZero figured out? As Garry Kasparov pointed out, “AlphaZero prioritizes piece activity over material,” as opposed to older engines that fixate on material. Learning entirely from playing against itself, absent any human preconceptions about strategy apart from the literal rules of chess, it seems to have developed its own strategic principles that place less emphasis on material and more on piece mobility.

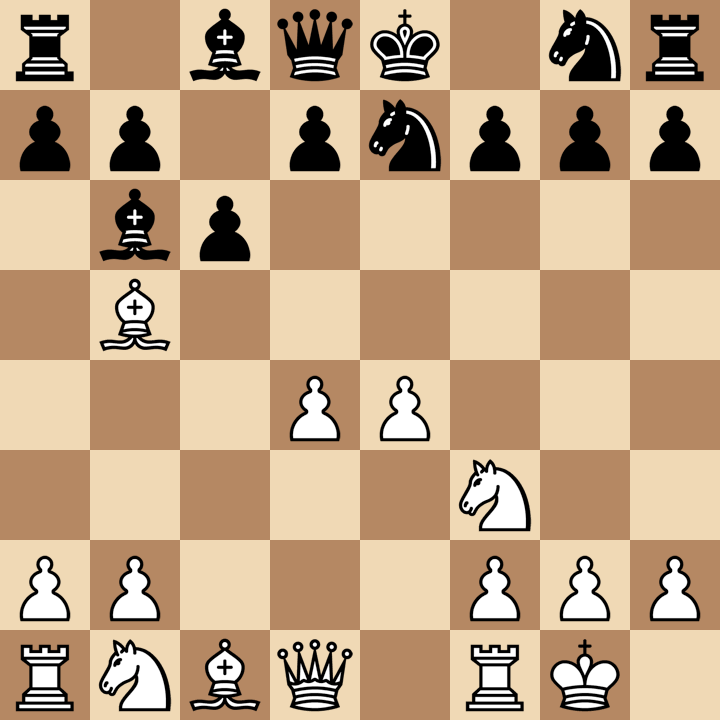

In this position white’s bishop is attacked and the normal thing to do would be to move it away. But LeelaZero (the open source implementation of AlphaZero) ignored the threat to the bishop and started pushing its d-pawn. After

d5 cxb5 2. d6

White was down a bishop, but had entombed black’s queenside pieces: Material for mobility.

LeelaZero converted this position into a convincing win. Black’s queenside pieces never got out.

This game was greeted with cries of “Insane!” and “Inhuman!” in the chess world. But why can’t we learn to prioritize mobility over material?

For many of us, one of the first things we’re taught about chess strategy is the point values of the pieces: Pawn = 1, Knight = 3, etc. This is appealing (to students and teachers!) because it’s simple, easy to understand, and easy to apply. Typically we only begin to understand piece mobility later, little by little. Even then, it never feels quite as solid, as scientific as those crisply defined piece values. As Jonathan Rowson says, “Material is the conceptual homeland to which we naturally return.”

It’s a typical pattern, not only in chess, that what is easy to measure becomes a stand-in for what matters. For instance, we use standardized tests for college admissions, not because they’re a terribly plausible measure of one’s potential as a student, but because they’re easy to compare across large numbers of applicants.

Imagine you’re writing a computer program to play chess. You decide to write a function to evaluate the current position. It’s easy to do this using material: simply add up all the piece values for one side and subtract that number from the same sum for the other side. What about a similar function for mobility? Maybe you take the difference of the legal moves available to each side. This seems to get at the core idea, but perhaps not quite capture it. Other concepts that are clearly important, like the initiative, are even harder to pin down. So I think material has become the standard evaluation metric, not because it’s necessarily the most important factor, but because it’s the easiest to measure.

It’s clear that some top players have taken this lesson to heart. In a recent game from the Russian Championship Superfinal, Danil Dubov sacrificed several pawns to paralyze his opponent’s queenside, much like in the LeelaZero game.

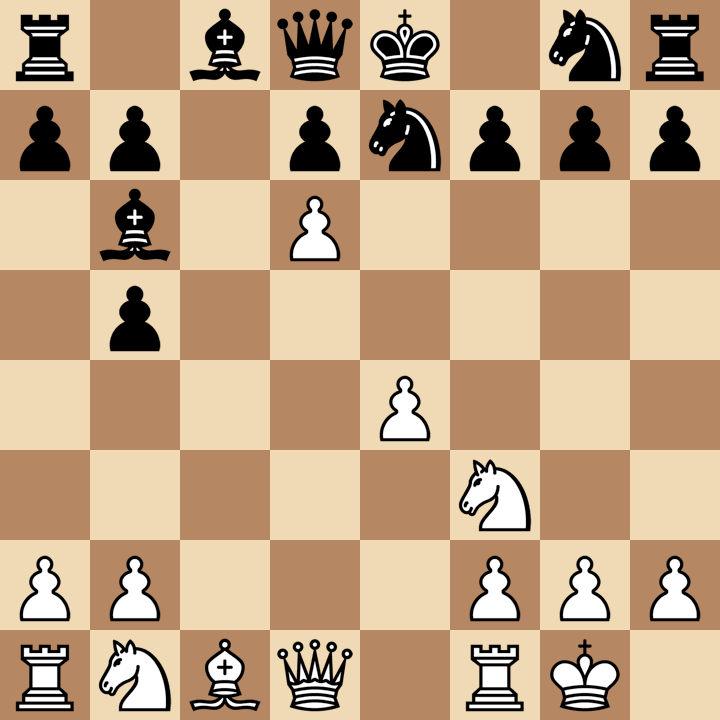

In this typical opening position, cxd4 and e5 have been seen many times, but Dubov played an unusual sequence sacrificing several pawns.

6. b4 Bb6 7. e5 Ne4 8. Bd5 Nxc3 9. Nxc3 dxc3 10. Bg5 Ne7

In the end he succeeded in tying down black’s queenside, very much like in the LeelaZero game.

Another reason we may feel more comfortable with a material advantage is that it’s a static advantage (according to the usual formulation), whereas mobility is dynamic. Even if our opponent’s pieces are restricted right now, we’re afraid they’ll eventually come out and we’ll have nothing to show for it. Mobility is temporary, material is forever. But in the two positions we’ve looked at, there seems to be a nearly static imbalance in piece mobility. It’s not just that black’s pieces haven’t gotten out yet, it’s hard to see how they can ever get out.

For most of us, opportunities to inflict our opponents with this sort of permanent paralysis aren’t fully baked into our intuition, but I don’t see why they can’t be. Perhaps a first step would be to consciously emphasize mobility during the game. A few times a game, you might remind yourself, “Mobility is more important than material. How could I restrict my opponent’s pieces, or expand the possibilities of my own?”

At the end of the day, I still don’t think there’s a fundamental law of chess. AlphaZero teaches us that, too. If there really were a few simple principles of chess that we knew how to articulate, it wouldn’t have taken so long for computers to get good: we would simply have programmed them with those principles and it would have been off to the races. Instead, it took huge advances in computing power for computers to out-calculate humans to such an extent that almost any rules would work.

Then AlphaZero came along and learned its own rules. Unfortunately, they’re not easy to understand, as they’re encoded as millions of numeric weights. Yet when you look at its games, the focus on piece mobility really does seem to be where it diverges from older engines like Stockfish. And as mysterious as all this sounds, I actually think incorporating this principle into your own play is quite feasible. Your execution won’t be on par with AlphaZero, of course, but simply accepting piece mobility as a first-class positional principle, on par or even ahead of material, is the first step.

Quite an insightful post. As my chess understanding is increasing, I am seeing the importance of this principle even more in my games. Material actually is a comfort zone for us humans as it gives us something tangible to hold on to in a game full of complexities. That's why I heed Kasparov's advice of playing gambits as beginners(Not always but from time to time) as they allow one to take risks and let go of material in exchange of rapid development and more dynamic chess play. I had a game today where I employed the smith morra against a Sicilian. Even though I was down a pawn, by Move 10 I had a big advantage (+2) due to strong activity of my pieces. I won comfortably after that.

When one can accurately see 30+ ply ahead as computers can, or can calculate at world championship level as the top players do, this emphasis on activity is a fine thing. When one is a mere mortal club player, the most gains are to be found in emphasizing accuracy in analysis and maximizing material. Strategy (of which activity is a major part) is the tie-break in choosing candidate moves in equally safe positions -- safety considerations dominate in almost all human games up to about master level.