The 2 Modes of Chess Thinking

Need a last second gift for a chess player? My Chessable courses are currently on sale!

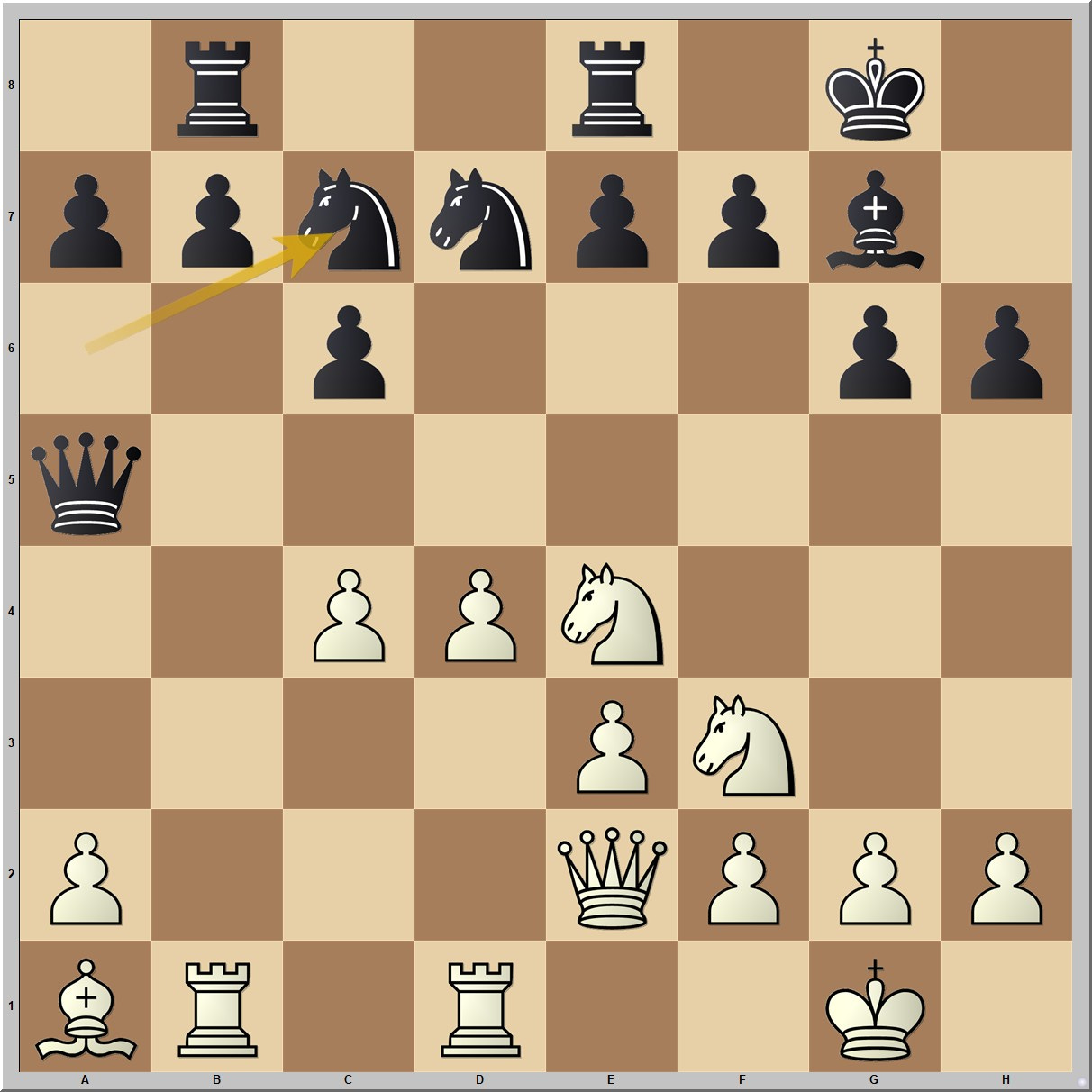

White to move. How do you evaluate the position, and what would you do?

I’m often asked what differentiates players of one level from players of another.

“What makes a 1600 better than a 1400?”

The truth is that everyone is different, and strengths and weaknesses vary tremendously, even at the same level. But one pattern I’ve noticed is that players in the 1800-2000 range are often comfortable with only one of the two modes of chess thinking, whereas masters are capable of working with both modes, and switching between them as needed.

Those two modes are move-based and idea-based thinking. Thinking in moves means working with specific sequences (you try to solve your problems with calculation). Thinking in ideas means working with concepts (you try to solve your problems abstractly).

Both modes have their rightful place, but I’ve found that players below master level tend to operate primarily (or even exclusively) with one mode. They may not even realize there’s another way of thinking.

In general, kids are more likely to be move-based thinkers while adults are more likely to be idea-based, but of course there are players of all types and ages.

Getting back to the position, my student had White. This student is a talented junior who loves to calculate. He went for 18. a4!? trying to exploit the Black queen’s lack of squares. This struck me as a move-based approach: he’s trying to trap the queen using forcing moves.

But while it’s a valid observation that Black’s queen is awkwardly placed and lacking squares, there is as yet no way to exploit this forcibly. Black could capture the a-pawn or ignore it. Either way, there’s no way to trap the queen, and it’s not clear if advancing the a-pawn will turn out to be useful.

In general, move-based thinking should be used when forcing moves (checks and captures) are present. When these options exist, you must calculate them. But when there are no forcing moves, or the forcing moves don’t work, that’s when you turn to idea-based thinking.

In particular, you could think about what advantages White has in the position. The biggest is the sturdy pawn center, which controls a lot of space and restricts Black’s pieces, especially the bishop on g7. In fact, the pawn center is enough to give White a healthy advantage.

If your natural mode is move-based thinking, your first instinct might be to set the center in motion with d5, but the forcing lines don’t work in White’s favor.

18. d5? Bxa1 19. Rxa1 (19. dxc6 Nf6! allows Black to remain up a piece by counterattacking the knight on e4) 19... cxd5 20. cxd5 Nxd5 is simply a pawn up for Black.

You could also argue conceptually that d5 doesn’t make sense, since it unblocks Black’s pieces, which was precisely the value of the pawn center in the first place.

A more subtle advantage of a solid pawn center is that it allows you to operate on the flanks with a higher degree of security. This leads to my favorite move in the position, 18. h4! This move combines a few ideas:

Make a luft for White’s king. You never know when that could be useful.

Soften up Black’s king position with h5 (perhaps after Bc3 or Ng3).

Take control of g5 in some lines.

This move isn’t a forcing win – the computer shows many moves of similar value – but it does ask Black some difficult questions. How big of a threat is h5? Should Black play h5 themselves to block it?

When you start asking your opponent tough questions, that’s when you can build up an advantage on the clock. I also believe that many blunders are caused by cognitive overload. The more you give your opponent to worry about, the greater the chance they make a big mistake.

Indeed, when my student and I tried to play out Black’s position against the engine, we had a hard time surviving five moves without a disaster. Try for yourself.

This is typical of my experience playing against the engine in “boring” positions: it is very difficult to survive more than a few moves. While some might find that depressing, I see it as a cause for optimism.

In a position where it looks like nothing is happening, you’re 1-2 good ideas and 3-5 great moves away from taking control.

Hi Nate

In the first line it should be move-based instead of idea-based:

In general, idea-based thinking should be used when forcing moves (checks and captures) are present. When these options exist, you must calculate them. But when there are no forcing moves, or the forcing moves don’t work, that’s when you turn to idea-based thinking.

My immediate reaction (in the initial position) was to try Bc3 with the idea of getting the white dark-squared bishop that seems to be white's worst piece out of the pawn chain.