Suffering like Nepomniachtchi

This is a man who’s about to win a World Championship, but he doesn’t look like he’s having fun. He’s got a great position. His queen is lurking near White’s open king, his pawn is strutting defiantly into enemy territory, his knight and rook stand poised to enter the attack. And yet a clear win is not so easy to find, at least without computer assistance.

A common piece of chess wisdom is to force yourself to apply maximum concentration when you think you’re winning. This is to counteract the natural tendency to become overconfident. Carlsen knows this, of course. He’s usually an intuitive player but when on the brink of victory he slows down to anticipate and block any possible escape route.

As Carlsen thought, he appeared to be matching wits with an empty chair. Ian Nepomniachtchi was backstage in his private rest room where he spent more and more time as the match went on. Fabiano Caruana, Carlsen’s opponent in the previous World Championship match and a commentator for this one, was critical of this habit. He said it reflected an inability to handle the tension of the match.

There hasn’t been this much commentary on a player’s absence from the board in a World Championship match since the infamous Toiletgate incident, when Veselin Topalov’s manager Silvio Danailov accused Vladimir Kramnik of spending too much time in his personal bathroom. He suggested that Kramnik was using trips to the bathroom to receive computer assistance, that being the only area not under video surveillance. After tense negotiations the match continued with Kramnik retaining his bathroom but forfeiting a game.

Zadie Smith wrote an essay titled “Suffering Like Mel Gibson” that uses the familiar meme of Mel Gibson talking to Jesus to explore different kinds of suffering during the pandemic. Ultimately, she concludes, suffering cannot be compared across individuals. Everyone’s is unique to themself. This feels apt for chess. Winning position, losing position, it’s all suffering.

The German grandmaster and longtime member of Carlsen’s team Jan Gustafsson said, “Chess is a constant struggle between my desire not to lose and my desire not to think.” For Nepomniachtchi it seems the desire not to think finally won out. He returned to the board only to record Carlsen’s move and make his desultory reply before retreating back to his lounge. He said he was thinking about his moves backstage, but evidently he wasn’t able to summon the needed concentration this way.

It has been said that talent is really just loving what you do. Maybe it consists even more in being able to tolerate the pain of what you do. Many new chess players got into the game through The Queen’s Gambit. While the show did an admirable job of portraying chess, it glossed over the amount of losing and associated suffering required to get good. The protagonist Beth Harmon breezes to the top of the chess world with setbacks that can be counted on one hand with a few fingers left over. Even Carlsen had to struggle for many years to become World Champion.

For the past few months I’ve been embarking on a long-envisioned project, learning a branch of abstract math. I didn’t make it very far with math in school, just one or two classes in college, but every time I would read about math in a popular article or book it seemed so interesting. Maybe, I thought, I just never had the right teacher. Maybe math was some sort of road not travelled. I settled on Group Theory on the advice of a chess-math friend. “If you can understand one thing about math, make it how Groups act on things.”

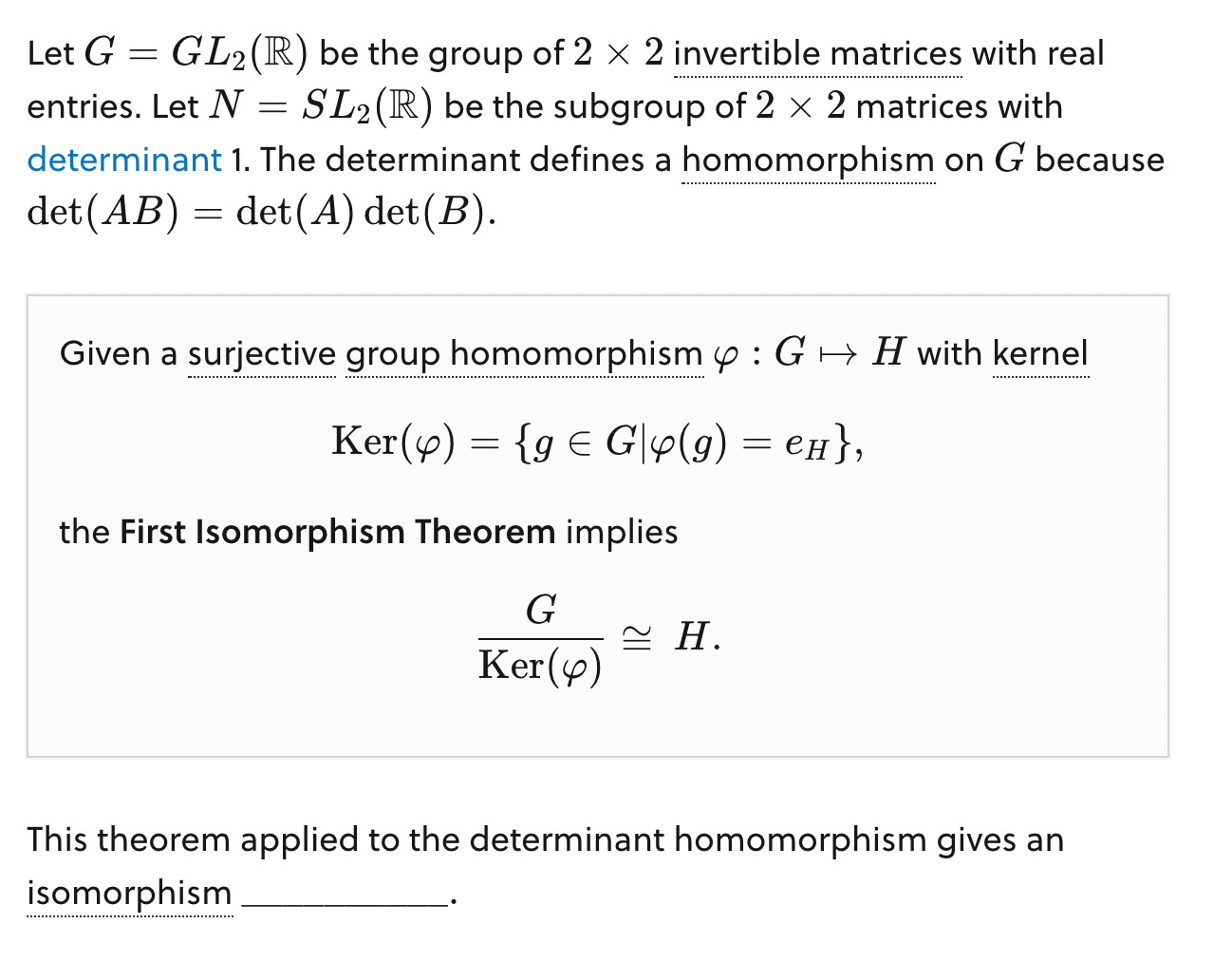

As it turns out, I’m not the Beth Harmon of math. Progress has been slow. I had hoped that at some point I would turn a corner, that math would begin to come easily to me, as chess seems to. This hasn’t exactly happened, although I continue to chug along. The more I think about it, the more my greater facility for chess seems like a greater ability to tolerate the pain that chess can dole out. I’m not a perfect chess player, obviously. I make lots of mistakes. But fundamentally I’m not scared to think about chess. Put a position in front of me and I’ll study it happily enough. In contrast, put something like this in front of me and it takes all my effort not to run away screaming:

Learning something deeply requires sustained focus and energy. With chess, I can devote most of my energy to studying the position. With math, my focus darts away, looks for ways to escape the pain of not understanding. All the balls that I was juggling in my head fall to the ground and I have to pick them up again one by one. Talent then is the ability to continue to sit at the board, to sustain an uncomfortable focus, to resist the temptation to go back to the players’ lounge.

The poker player Jack Strauss said, “If I lose, I don’t give a damn about the money, but I just hate the embarrassment of being beaten.” For many players, what’s worse than the loss itself is the embarrassment, being made to look stupid or weak. As he looked for the knockout blow, did Magnus contemplate the embarrassment of failing to win from such a promising position? Do such thoughts even enter his mind? Or does the sweet swimming pool of victory wash them away?

For once, Magnus did not find the best move. One of his few weaknesses, if it can be called that, is that sometimes he gets lost in the poetry of his pieces when it’s entirely possible to hit his opponent in the head with a wrench. He moved his knight to f5, a lovely square to be sure, but a simple pawn capture would have ended the game directly.

1…exf2+ and then:

A) 2. Kxf2 Qh2+ loses the queen to a skewer.

B) 2. Qxf2 Rd6 and there is no good way to stop the rook from swinging over to g6 with a deadly check.

Carlsen’s move didn’t let the win slip, it just prolonged the process. For Nepomniachtchi, the suffering would continue into the endgame.

If you’ve been enjoying Zwischenzug, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. You’ll be supporting my writing and get access to additional chess content and perks. More info here.