Earlier this week world champion Magnus Carlsen made an unexpected appearance in Titled Tuesday, Chess.com’s weekly blitz tournament for titled players. Unexpected because Magnus usually sticks to tournaments organized by his own Play Magnus group, or Lichess, whose aversion to money allows them to maintain a sort of neutrality. From a business perspective Chess.com is his biggest rival, but when it comes to chess Magnus does what he wants.

Politics aside, Magnus won the tournament with 10/11. What’s really interesting to me is how he is able to dominate such strong opponents so consistently. That’s what we’ll try to figure out today by diving into the games.

Take your opponent out of their comfort zone

In this standard opening position vs. Tania Sachdev, Magnus as Black initiated a series of exchanges to radically unbalance the position.

4… Bb4+ 5. Bd2 Bxf3 6. exf3 Bxd2+ 7. Qxd2 d5

As a result of the exchanges, the position is highly imbalanced. White has doubled pawns and likely, after a pawn exchange in the center, an isolated d-pawn, which could become a major weakness in the long run. On the other hand, the unopposed light-squared bishop could become a monster. It’s a strategically fraught position where mindless development won’t get the job done.

The extent to which this took Tania out of her comfort zone can be seen on the clock. She spent 12 seconds on her next move, 8. Nc3, and after Magnus’ reply 8… Ne7 an additional 30 seconds - an eternity in a 3-minute game - on the pawn exchange 9. cxd5. Neither of these moves are mistakes, but it shows that she was already uncomfortable in the position and felt compelled to burn time that could have been useful later.

Mikhail Tal famously said, “You must take your opponent into a deep dark forest where 2+2=5, and the path leading out is only wide enough for one.” With Tal we think of tactical complications, but Magnus pursues a similar strategy strategically. He forces nonstandard strategic situations where the usual rules don’t apply, then uses his deep and broad strategic understanding to outmaneuver his opponents.

Always be improving

From this standard looking position vs. Petros Trimitzios, Magnus as Black played seven improving moves in a row… And got a winning position!

15… h6 16. Rd2 Rd7 17. Rcd1 Rad8 18. h3 Qe4 19. Kf1 a5 20. a3 Be7 21. Ra1

It seems like nothing has really happened, but mysteriously all of Black’s pieces have gotten better while White’s have gotten worse. The rook on a1 is stuck defending the a3-pawn and the rest of White’s pieces are trying to hold onto the d-pawn. Now Magnus sprung into action.

21… f5

Objectively not the best move, since it allows 22. Bf4! with the point 22… Qxf4 23. Qxe6+ when White would win the knight on c6 with a good position, but understandably in a blitz game this was missed.

22. Qd3 Qxd3 23. Rxd3 e5

Now Black is threatening a fork with e4, as well as simply taking the d-pawn. White has no good way to hold everything together and Magnus cruised to a win from here.

It’s remarkable how Magnus is able to defeat strong opponents without “doing” anything. In one sense, this comes down to playing with a plan. Magnus was able to organize his play around pressuring the d-pawn, while White lacked a clear idea of how to improve his position. Then again, several of Magnus’ moves, like h6 and a5, weren’t really connected to pressuring the d-pawn, but just generically useful moves, eliminating back rank mates and gaining space on the queenside.

In addition to playing with a plan, it seems to me that equally relevant is the idea of “do no harm” - avoiding moves that make your position worse. For example, White’s move a3 created an additional weakness on the queenside that, combined with the weakness on d4, stretched his defenses too thin. In addition to improving your own position, small improving moves often prod your opponent into making their own position worse.

As always, easier said than done. For instance, why was Black’s a5 an improving move and White’s a3 was a weakening move? Well, a3 created a weakness that could be attacked by Black’s pieces, whereas a5 does not create any new targets White can exploit. Interestingly, a5 links up a chain of 3 pawns protecting each other, while a3 unlinks a 3-pawn chain. Not the usual vocabulary I’d use to think of pawn structure, but maybe it should be?! It seems relevant here. In any case, sensing these kinds of differences is what makes Magnus Magnus!

Be opinionated

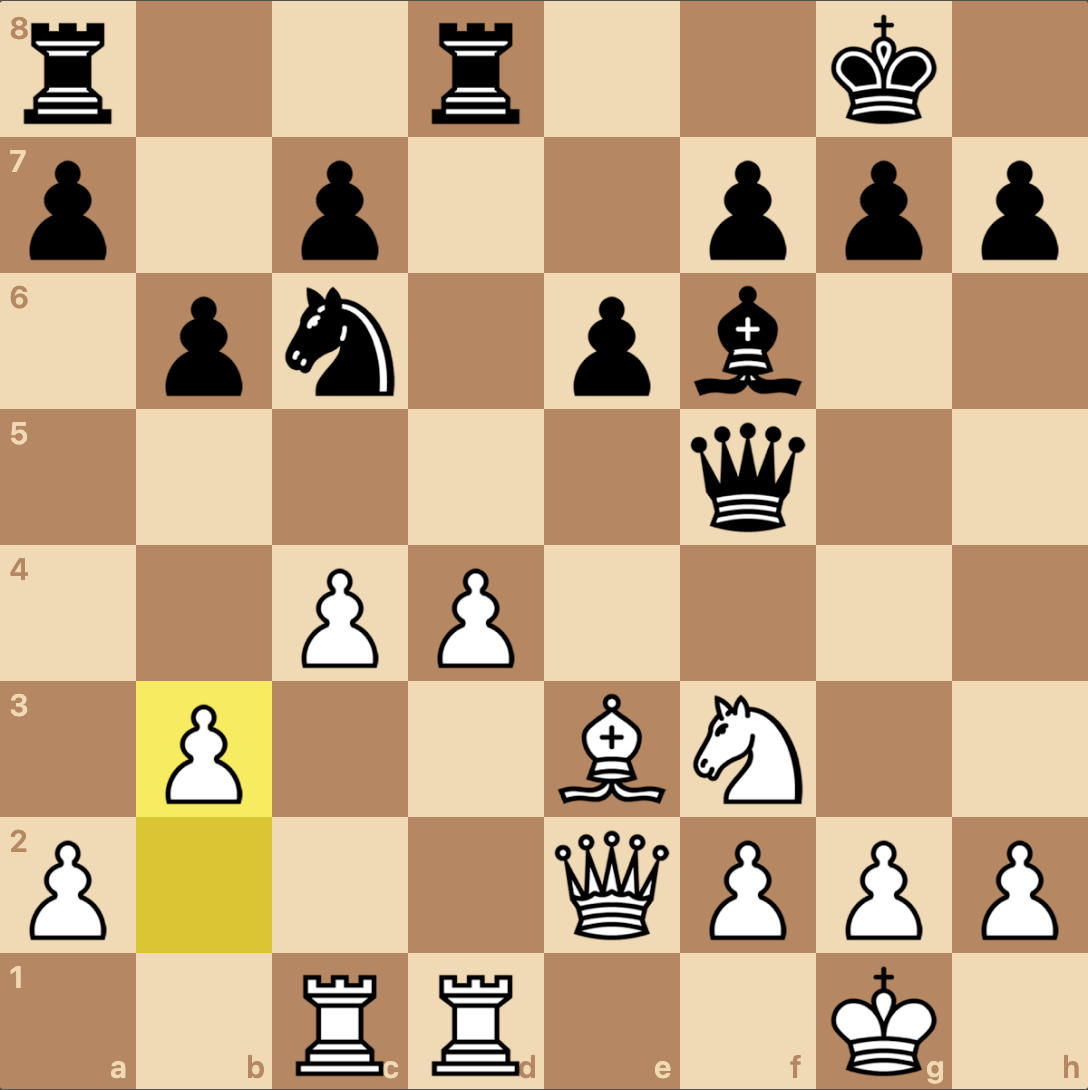

In this position with Black against GM Alexander Fier, Magnus clearly has the upper hand. He has control of the only open file, the better pawn structure, and better minor pieces (White’s bishop isn’t doing much). Still, it’s not easy to see how to improve the position. Magnus’ next move opened a second front.

29… g5!

Many players would be nervous to open up their own king position, but Magnus correctly judges that he’s the one who will be attacking on the kingside. He soon crashed through with a knight sacrifice.

30. hxg5 Qxg5 31. Rg1 Ndf6 32. Nd1 Ra3 33. Qe2 Kh8 34. Ne3

34… Nf4! 35. gxf4 Qh4+ 36. Kg2 Nh5 37. Qc2 Nxf4+ 38. Kf1 Qh3+ 39. Kf2 Nxd3+ 40. Ke2 Nf4+ 41. Kf2 Qh2+ 42. Ng2 Nh3+ 43. Ke2 Qxg1 0-1

Maybe Magnus’s most distinctive trait is his ability to get to the heart of the position. That’s what I get from the move g5: a clear vision of what the position’s about and how the game will progress.

Can us mere mortals take anything useful from Magnus’ blitz games? I think we can. For computers, moves may be simply moves, but for humans, to consistently find good moves we need them to be connected to ideas. For that reason whether we’re playing or analyzing we need to be constantly trying to get to the heart of the position to figure out the one thing it’s really about.