“The ability to play chess is the sign of a gentleman. The ability to play chess well is the sign of a wasted life.” - Paul Morphy

Paul Morphy was born in 1837 in New Orleans into a wealthy family. He learned chess by watching his father and uncle play. They found out he knew the rules when he pointed out a win his uncle had missed. By age nine he was considered one of the best players in New Orleans. As a young man, he won a tournament featuring the best players in the United States. Then he went on a tour of Europe, the home of the best players at the time, but they didn’t prove much more of a challenge. He would play multiple opponents at once, or blindfolded, or with material odds; he usually won anyway. Upon returning to New Orleans he quit competitive chess.

The next act in his life was to be practicing law. This decision does not appear to have been based on financial concerns: he was already supported by his family’s fortune. Rather, he seems to have felt that chess wasn’t a sufficiently serious occupation to devote his life to. But his law office went nowhere: all his visitors just wanted to talk about chess.

When I visited Morphy’s grave on a trip to New Orleans, I couldn’t help but think that, with the benefit of hindsight, the decision to abandon chess had been a blunder. He may have considered the law a more serious calling, but ultimately his law career was dilettantish and rather pointless. In contrast, his chess was incisive, energetic, and many years ahead of its time. Chess players still learn how to coordinate their pieces and attack by studying his games – but few of them were recorded. One can only imagine what he would have accomplished if he kept playing. Almost certainly, he would have been the first world champion. The title was created while he was alive, but no longer playing.

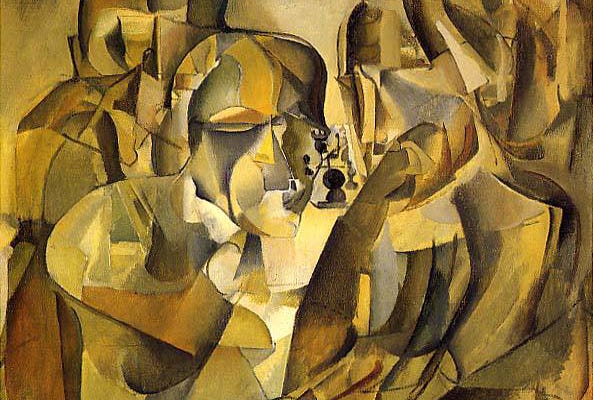

The Soviet grandmaster David Bronstein, who was one game away from being world champion, said, “I regret that I devoted my life to chess, and not to something like art.” I always found it odd that Bronstein, the most creative of chess players, didn’t consider chess itself to be a form of art. After all, it was Marcel Duchamp who said, “While all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.”

The grass is always greener on the other side. You tend to be keenly aware of the annoyances of your own field, while entertaining an idealized picture of others. Bronstein may have imagined the life of an artist as idyllic, but Duchamp knew how petty the art world could be. He was one of the most influential and successful artists in the world, but walked away from art to pursue chess.

Duchamp was no casual chess player. He studied for hours a day, regularly competed in tournaments, and published endgame studies. For Duchamp, the absence of a clear end goal in chess represented not sterility, but purity: “Chess has no social purpose. That, above all, is important.”

Albert Einstein asked of the second world champion Emanuel Lasker, “How can such a talented man devote his life to something like chess?” Lasker was also a trained mathematician and made contributions to commutative algebra, but chess remained his primary calling. He retained the world championship for 27 years.

It would be hard to imagine someone whose work was more self-evidently important than Einstein. He completely reimagined the most fundamental properties of physics in ways that reshaped our understanding of the world and led to countless technological advances. When chess players imagine being scientists, they probably imagine being Einstein.

Yet even Einstein, you could say, was rarely Einstein. He made most of the discoveries he’s famous for in a single year, when he was 26. He spent the second half of his life trying (unsuccessfully) to reconcile his theories with quantum mechanics. And even the monumental impact of his work seems to have been little balm for regrets near the end of his life. In a letter written shortly before his death, he confided to a friend, “The exaggerated esteem in which my lifework is held makes me very ill at ease. I feel compelled to think of myself as a swindler.”

I have noticed that many of the adults I coach seem reluctant to schedule over-the-board tournaments. Part of this, of course, is just the difficulty of carving out a weekend from work and family life. But I believe there’s something deeper as well. Scheduling a multi-day tournament would mean admitting to yourself (and your spouse, who has to watch the kids) that you take chess seriously. For many adults, this is a difficult bridge to cross, even though of course they’re already spending as much time and more pursuing chess in less deliberate ways.

For those conflicted about their relationship to chess, I would suggest an unusual tactic: consider quitting. Really consider it. Many people say they are “addicted” to chess, but you could quit if you really made up your mind to. What would you do with your newfound time? Would your life be better?

Many chess players dream of quitting to pursue a higher calling, but Santiago Ramón y Cajal actually did it. The Spanish scientist was accustomed to spending a lot of time at the Casino Militar, a social club where chess and other games were popular. But at the same time, Ramón y Cajal was developing new microscopic imaging techniques. He began to see intriguing details in nerve cells that contradicted the accepted theories at the time. Sensing he was on to something, he resolved to go all-in on his scientific career, which meant giving up chess. He went on one last binge in which “he allowed himself the delicious joy of defeating his adversaries by ingenious tricks for a whole week.” Then, for the next 25 years, he avoided chess.

For Ramón y Cajal, unlike for Morphy, switching his focus away from chess proved fruitful. He developed a theory of neuroanatomy that upended the assumptions at the time, and was ultimately borne out by the evidence. Today he is regarded as the father of modern neuroscience and his drawings are still used to train new scientists. If the two great mysteries for science are the cosmos and the brain – looking inward and outward, so to speak – you could argue that Ramón y Cajal’s impact was as great as Einstein’s, although his name is not as well-known today.

It strikes me that many of the great scientists of the past few centuries were enthusiastic chess players. Despite his dig at Lasker, Einstein seems to have been quite a decent player himself. Claude Shannon, the pioneer of information theory, was a prolific player and wrote a seminal paper on programming a computer to play chess. According to one study, the more distinguished a scientist is in their field, the more likely they are to have intense hobbies. I wonder if one reason for the persistent fascination with chess is that it provides a sort of training in structured thinking.

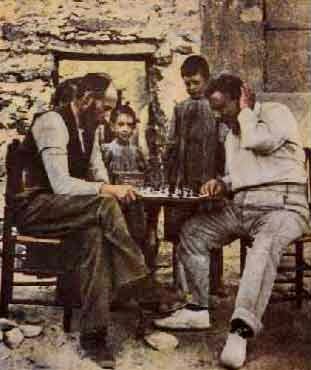

Ramón y Cajal may not have avoided chess as assiduously as he sometimes claimed. In 1898, ten years into his 25-year abstinence, a picture was taken of him playing chess while on vacation with a friend. He is studying the board, apparently calm, focused, and engaged. Two children stand behind the board, watching the game.

Another good example:

Ken Rogoff.

This post sold me on subscribing. Thank you.