Chess is 90% taking pieces. Rearranging your guys is cool and all, but when wood starts coming off the board, it’s a whole different story.

Having more pieces than your opponent (or more valuable pieces) is a huge advantage because it’s simple and durable. As long as nothing crazy happens, if you have better pieces, you will win in the long run.

I get the feeling my students never quite believe me when I say this, but I mean it:

If you take your opponent’s pieces, and don’t let them take yours, you can beat almost everyone.

Despite this being such a huge part of the game, the simple act of taking pieces gets relatively little attention in chess literature. Most authors are eager to move on to more advanced topics like tactics and strategy, but the truth is, few players below master level have fully mastered the art of taking pieces.

As usual, the peerless Dan Heisman is ahead of the curve here with several videos and articles on what he calls “counting”, i.e., sequences of captures. Getting disoriented in sequences involving multiple captures is probably the single biggest kind of mistake that causes my students below 1600 to lose games.

Capture problems can be sorted into a hierarchy:

Hanging pieces (do you know everything that can be taken?)

Sequences of captures on one square

Sequences of captures on multiple squares

The first level is relatively simple, but still takes a lot of practice to master. If you are unaware of a hanging piece even a small percentage of the time, it can still easily cost you the game. For players stuck below 1000, the culprit is often devoting all their study time to more advanced tactics, when they haven’t fully mastered hanging pieces.

The next level, sequences of captures on one square, can often be resolved simply by counting attackers and defenders. Nonetheless, beginning players often become overwhelmed and make errors evaluating these sequences.

The third level, captures on multiple squares, can get extremely complex, often posing problems even for master level players.

Let’s see some examples!

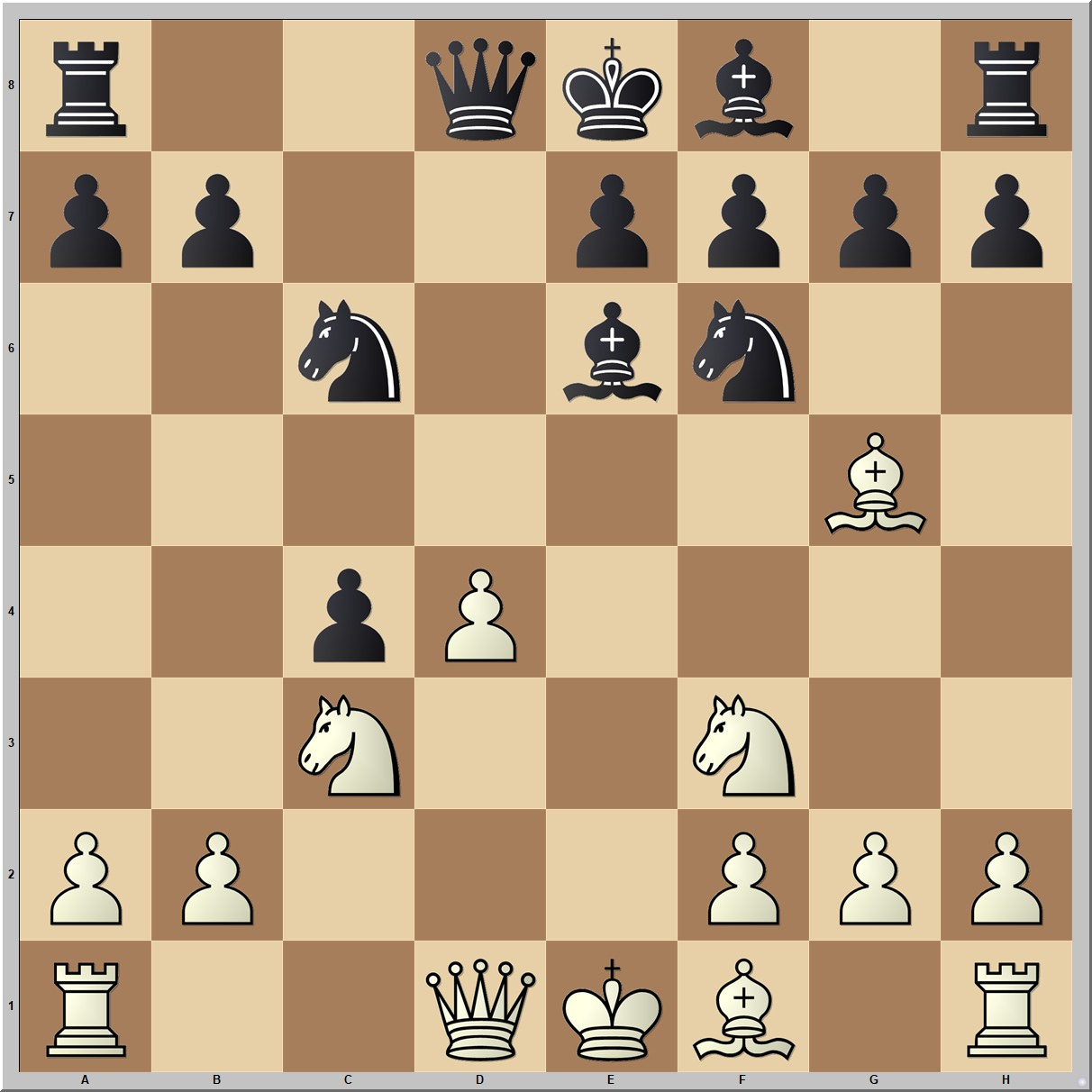

Example 1

If you practice your pattern recognition, the possibility for a pawn fork with d5 should jump out at you. However, the immediate 1. d5 doesn’t work, because Black has enough attackers to come out on top in the sequence of exchanges. For example, 1. d5 Nxd5 2. Nxd5 Qxd5 3. Qxd5 Bxd5. Crossing out equal trades, Black won a pawn in this sequence.

Sequences of captures on the same square (as in d5 in this example) are the easiest to handle, but even these can present a big challenge to newer players. In lessons, many players get overwhelmed or frustrated and abandon these sequences before reaching the end of the captures.

There are two ways to approach this kind of sequence:

The standard calculation approach: go through the moves one-by-one, maintaining a clear picture of the position in your head. This is very versatile and powerful, but the ability to visualize multiple moves into the future takes practice to build up.

The shortcut approach: count the number of attackers and defenders; if the attackers outnumber the defenders, the attacking side will make the last capture and come out on top. This is much easier, but you need to be careful of the sequence of captures: if you send the queen in first, you might make the last capture, but still get the short end of the stick because you lost your best piece.

In this case, you can use either approach to verify that 1. d5 doesn’t work. However, inserting 1. Bxf6 first removes a defender from d5, after which the pawn fork works. In the game, White alertly spotted this possibility, won a piece, and went on to win the game. But I’ve found that innocuous captures like Bxf6 are often missed.

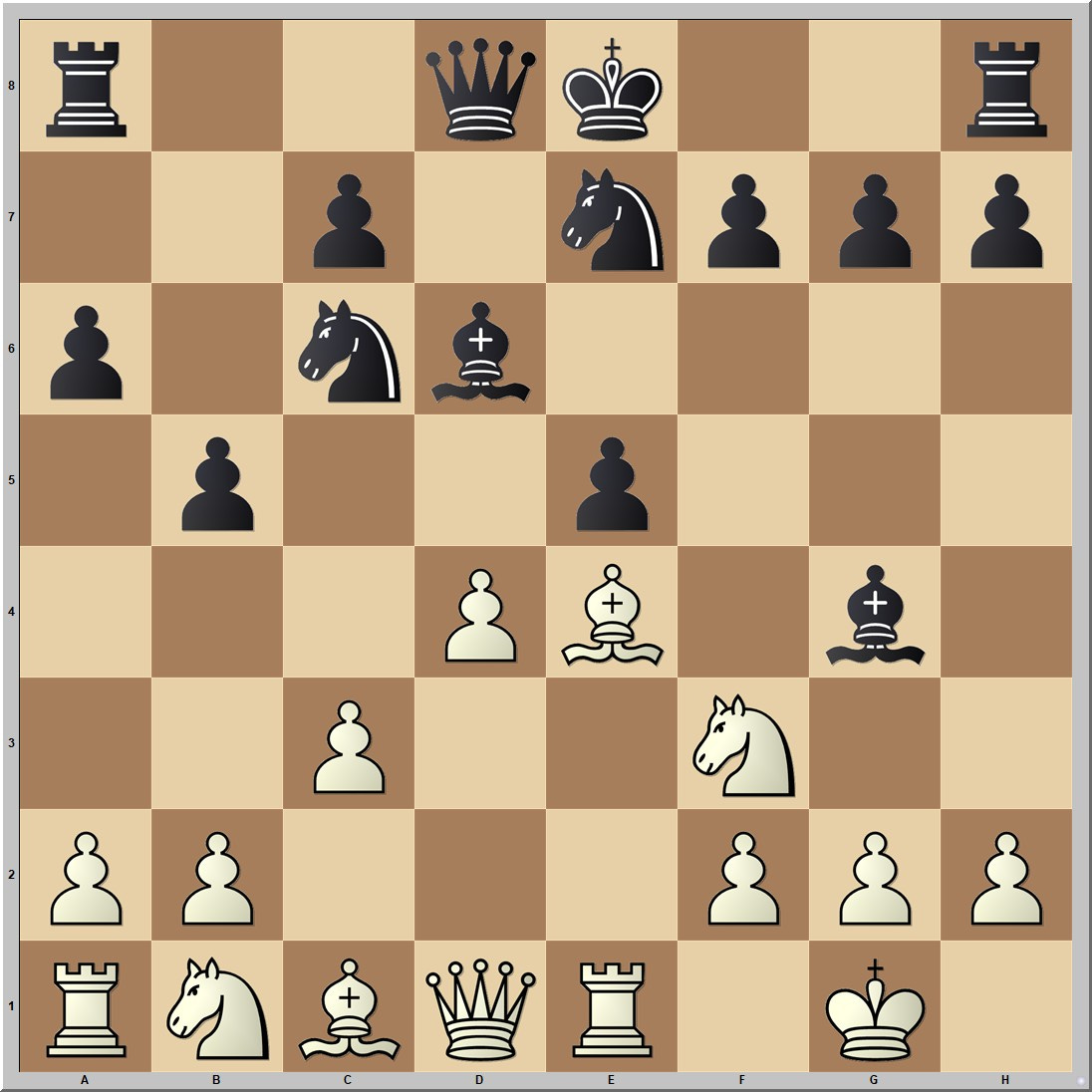

Example 2

If you think captures are simple, consider the next position. What is White’s best continuation?

The most obvious capture, 12. dxe5, is good, but allows Black to stay in the game. After either 12... Bc5 or 12… Nxe5 13. Bxa8 Qxa8, Black is worse, but still kicking.

Far more devastating, but less obvious, is 12. Bxc6+ Nxc6 13. Nxe5! Now Black has many possible captures, but no way to avoid losing at least a piece. For example:

13... Nxe5 14. Qxg4 when the pin along the e-file guarantees White an extra piece.

13… Bxd1 14. Nxc6+ Kd7 15. Nxd8 Raxd8 (or 15… Bh5 16. Nb7) 16. Rxd1 and White again emerges with an extra piece.

This is much trickier than the previous example, because the captures are happening on different squares. In this case, you can’t shortcut the process by counting attackers and defenders; you just have to calculate and visualize the positions. Even masters often struggle to calculate this type of sequence accurately.

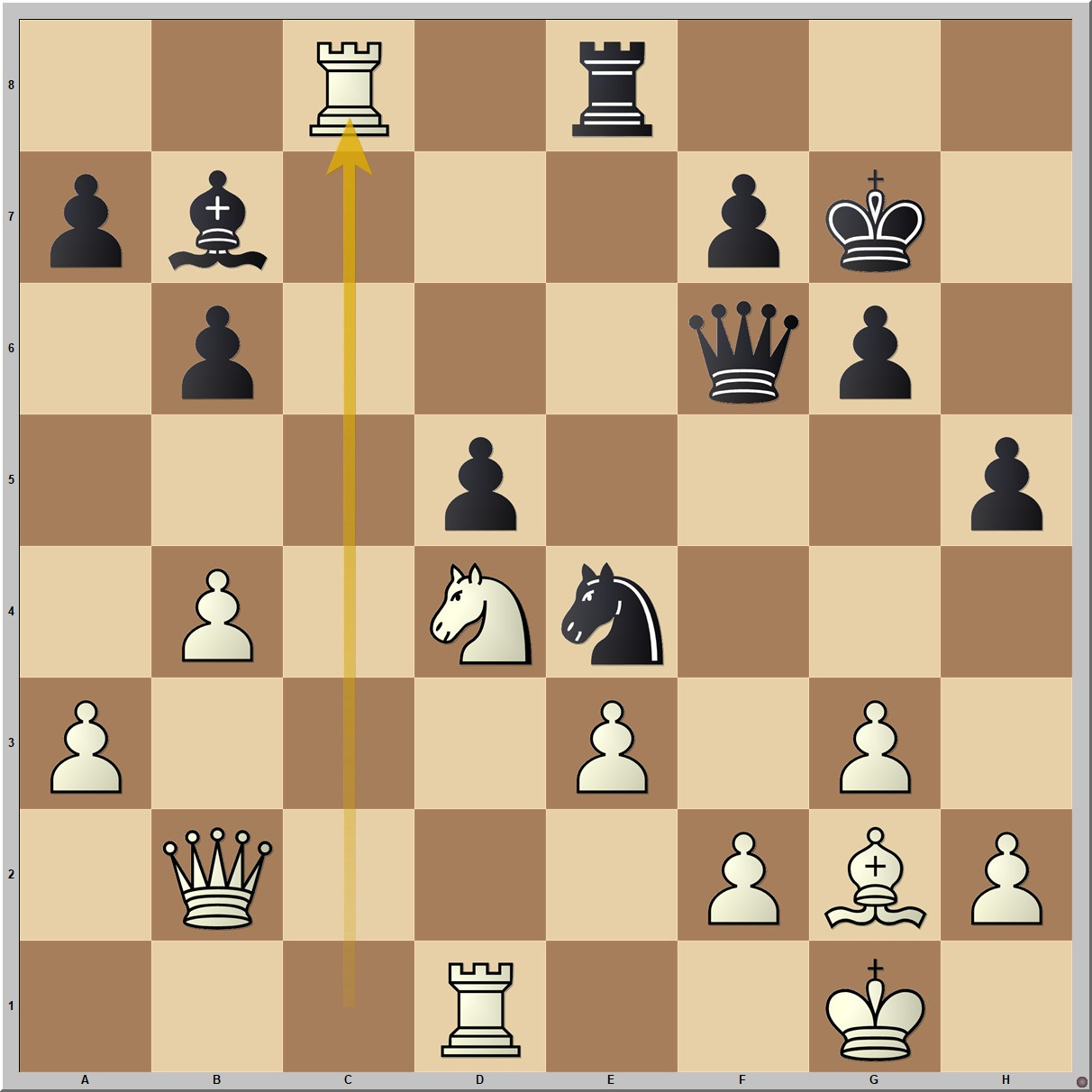

Example 3

Even Magnus Carlsen occasionally forgets to account for captures. In this position, Carlsen chose to recapture with the rook, Rxc8. Putting a rook on an open file is often positionally desirable, but in this case it was a losing blunder.

Ruud Makarian, playing the White pieces, seized his opportunity with 25. Bxe4 dxe4 26. Ne6+! Carlsen resigned because after 16… fxe6 17. Rd7+ the king has to give up its defense of the queen, and White will play Qxf6 with a huge material advantage.

Normally Carlsen would spot this kind of deflection tactic without breaking a sweat, but in this case it was “hidden” behind an innocuous-seeming capture, and that was enough to cause a moment of blindness.

Conclusion

For how critically important captures are to winning (and losing) chess games, there really aren’t a lot of ways to practice them. Captures aren’t counted as a “tactic” alongside things like pins and forks (although they probably should be). I’ve been saving a lot of these positions in lessons, but it will take me a while to have enough for a book or course.

One way to practice would be to use the Lichess Hanging Piece puzzle theme with the difficulty set to Easier or Easiest. On the standard level, I find the puzzles are still too complicated: they start with a hanging piece, but that’s only the beginning of a complicated sequence. What many players need help with is simply taking pieces consistently.

On the upside, possibilities for captures are so common that you can learn a lot just by studying your own games. These scenarios come up in every single game. When you’re playing, always consider captures, and when you review after the game, make sure you understand why sequences of captures are good or bad.

First OBIT (Openings, Blunders, Interesting, Takeaway), now CREAM... it's NATE! (Numerous Acronyms Towards Excellence)

Get the Money. Dollar Dollar Bills Y’all.